The 'Science' of Cartography is Limited - Mapping Belfast's Myths

PLACE - 7-9 Garfield St, Belfast 20 April - 5 May 2017

Over the course of my doctorate I developed a practice-based mixed methodology highlighting the importance of tacit poetic interpretations when it comes to spatial understanding, I examined a series of mappings of Belfast and attempted to map the city myself. This exhibition brought together these mappings – planning documents, architectural proposals, GPS tracings and films – allowing their successes and failures to be assessed.

Exhibition Boards

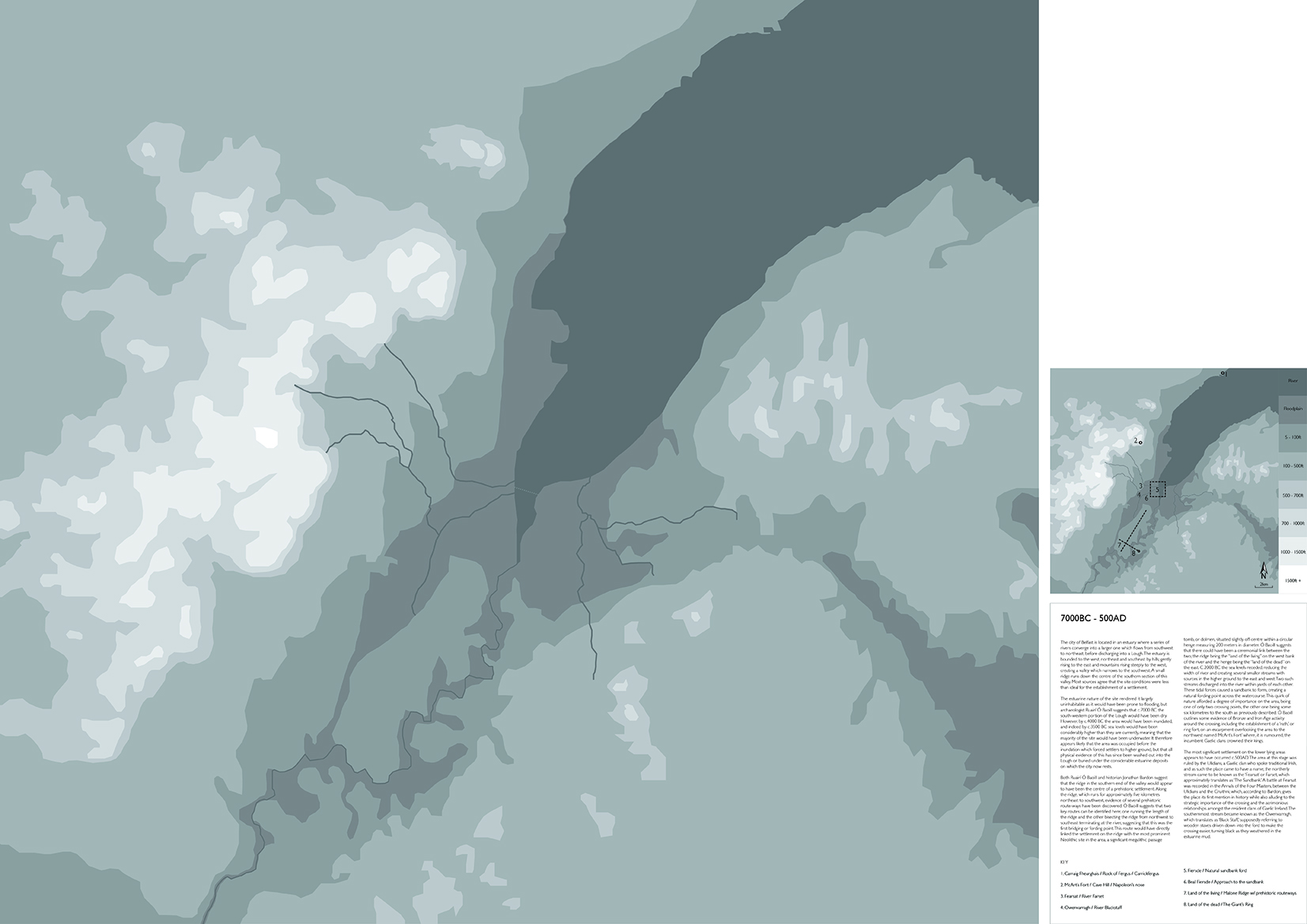

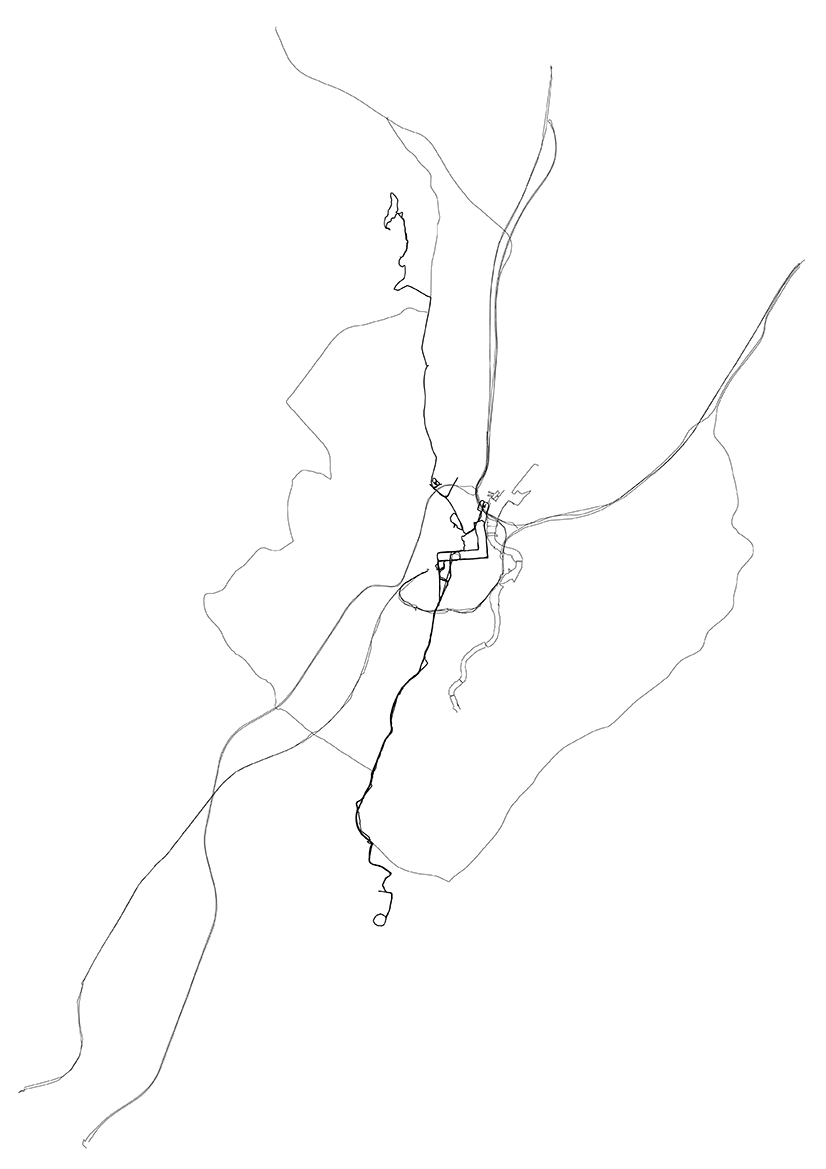

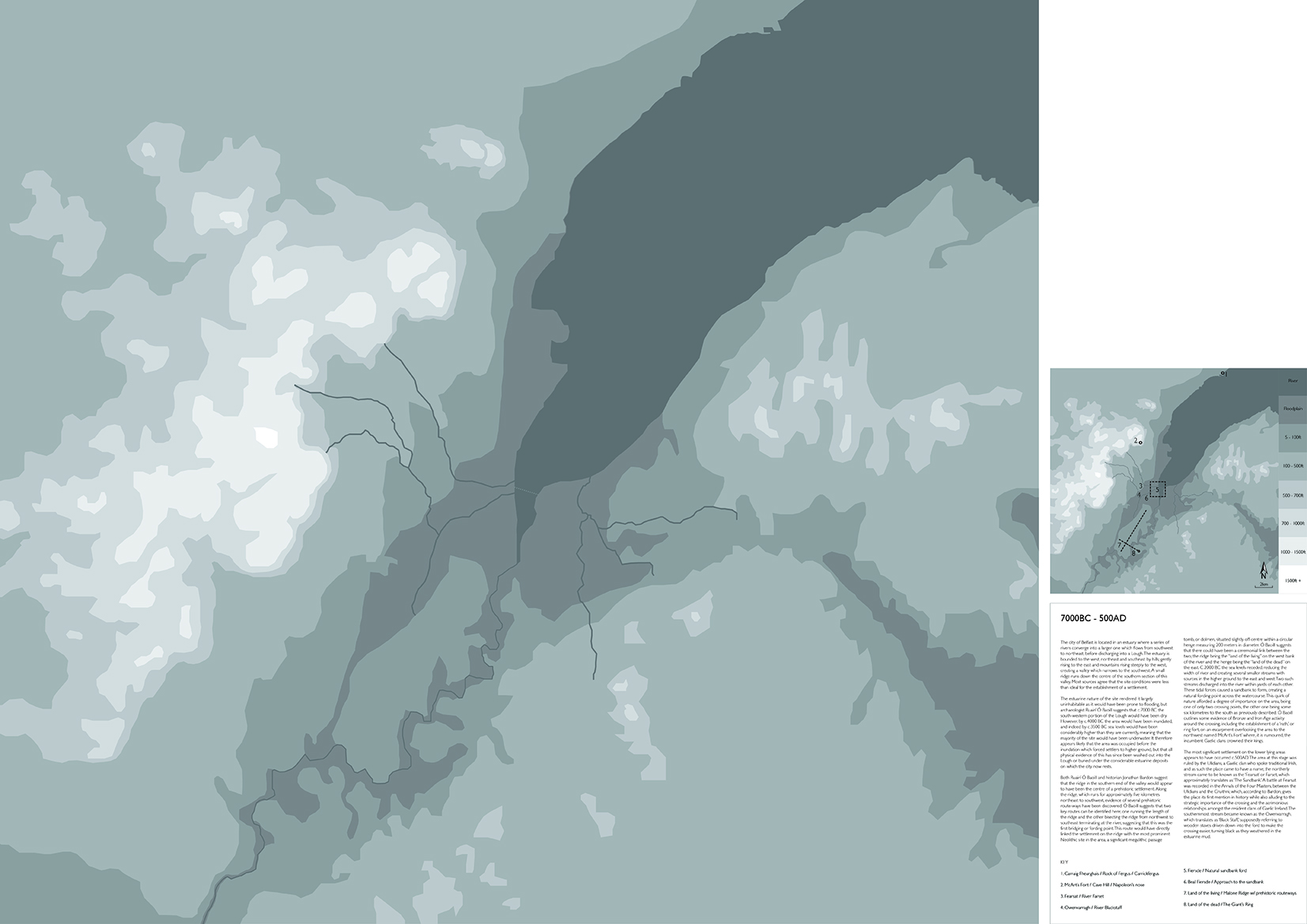

The city of Belfast is located in an estuary where a series of rivers converge into a larger one which flows from southwest to northeast, before discharging into a Lough. The estuary is bounded to the west, northeast and southeast by hills; gently rising to the east and mountains rising steeply to the west, creating a valley which narrows to the southwest. A small ridge runs down the centre of the southern section of this valley. Most sources agree that the site conditions were less than ideal for the establishment of a settlement. The estuarine nature of the site rendered it largely uninhabitable as it would have been prone to flooding, but archaeologist Ruairí Ó Baoill suggests that c.7000 BC the south-western portion of the Lough would have been dry. However, by c.4000 BC the area would have been inundated, and indeed by c.3500 BC sea levels would have been considerably higher than they are currently, meaning that the majority of the site would have been underwater. It therefore appears likely that the area was occupied before the inundation which forced settlers to higher ground, but that all physical evidence of this has since been washed out into the Lough or buried under the considerable estuarine deposits on which the city now rests. Both Ruairí Ó Baoill and historian Jonathan Bardon suggest that the ridge in the southern end of the valley would appear to have been the centre of a prehistoric settlement. Along the ridge, which runs for approximately five kilometres northeast to southwest, evidence of several prehistoric route-ways have been discovered. Ó Baoill suggests that two key routes can be identified here; one running the length of the ridge and the other bisecting the ridge from northwest to southeast terminating at the river, suggesting that this was the first bridging or fording point. This route would have directly linked the settlement on the ridge with the most prominent Neolithic site in the area, a significant megalithic passage tomb, or dolmen, situated slightly off-centre within a circular henge measuring 200 meters in diameter. Ó Baoill suggests that there could have been a ceremonial link between the two; the ridge being the “land of the living” on the west bank of the river and the henge being the “land of the dead” on the east. C.2000 BC the sea levels receded, reducing the width of river and creating several smaller streams with sources in the higher ground to the east and west. Two such streams discharged into the river within yards of each other. These tidal forces caused a sandbank to form, creating a natural fording point across the watercourse. This quirk of nature afforded a degree of importance on the area, being one of only two crossing points, the other one being some six kilometres to the south as previously described. Ó Baoill outlines some evidence of Bronze and Iron Age activity around the crossing, including the establishment of a ‘rath,’ or ring fort, on an escarpment overlooking the area to the northwest named ‘McArt’s Fort’ where, it is rumoured, the incumbent Gaelic clans crowned their kings. The most significant settlement on the lower lying areas appears to have occurred c.500AD. The area at this stage was ruled by the Ulidians, a Gaelic clan who spoke traditional Irish, and as such the place came to have a name; the northerly stream came to be known as the ‘Fearsat’ or Farset, which approximately translates as ‘The Sandbank.’ A battle at Fearsat was recorded in the Annals of the Four Masters, between the Ulidians and the Cruithni, which, according to Bardon, gives the place its first mention in history while also alluding to the strategic importance of the crossing and the acrimonious relationships amongst the resident clans of Gaelic Ireland. The southernmost stream became known as the Owenvarragh, which translates as ‘Black Staff,’ supposedly referring to wooden staves driven down into the ford to make the crossing easier, turning black as they weathered in the estuarine mud.

KEY 1. Carraig Fhearghais / Rock of Fergus / Carrickfergus 2. McArt’s Fort / Cave Hill / Napoleon’s nose 3. Fearsat / River Farset 4. Owenvarragh / River Blackstaff 5. Fiersde / Natural sandbank ford 6. Beal Fiersde / Approach to the sandbank 7. Land of the living / Malone Ridge w/ prehistoric routeways 8. Land of the dead / The Giant’s Ring

Sir Alfred Brumwell Thomas made a set of propoals for the city in the interwar years. Belfast City Hall is considered Thomas’ greatest achieve- ment and, along with the Royal Avenue development, provided Belfast – an industrial town which lacked a civic tradition up to this point – with a civic focus. The widening of the Hercules Lane into the broad commercial boulevard of Royal Avenue is arguably the earliest and still most significant piece of urban design in the city. This street layout created a cruciform street pattern with Wellington Place and Chichester Street, forming what the Belfast Metropolitan Area Plan refers to as the Belfast Cross. The City Hall sits at the centre point of the cross; the most important civic building sitting at the apex of the most significant civic thoroughfares situated in the Beaux Arts civic tradition. Thomas hoped to carry this tradition into the twentieth-century with a new civic proposal bringing May Street and Howard Street into the Belfast Cross. Thomas explained that this would be accomplished by creating new parks at either end of these two thoroughfares, one arranged around the Royal Courts of Justice and the other at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution. This proposal would form what the Northern correspondent of the Irish Builder refers to as a “triple square plan,” with Donegal Square forming the central plaza. These squares would be “beautified” with significant and noble buildings to the standards set by the City Hall. One such building was the unrealised Royal Ulster Hotel, proposed again by Thomas to be located on Donegal Square East between the Methodist Church (now Ulster Bank) and the Ocean Finance building (now Pearl Assurance House). Thomas drew up plans, secured the land and established a company to finance the construction of the hotel, but these plans went awry as Thomas fell out of favour with Belfast Corporation, also losing the commission for the design of Belfast’s war memorial located on Donegal Square West mid-way through it’s construction. Despite these plans, Thomas’ involvement with the city begins and ends with the construction of the City Hall.

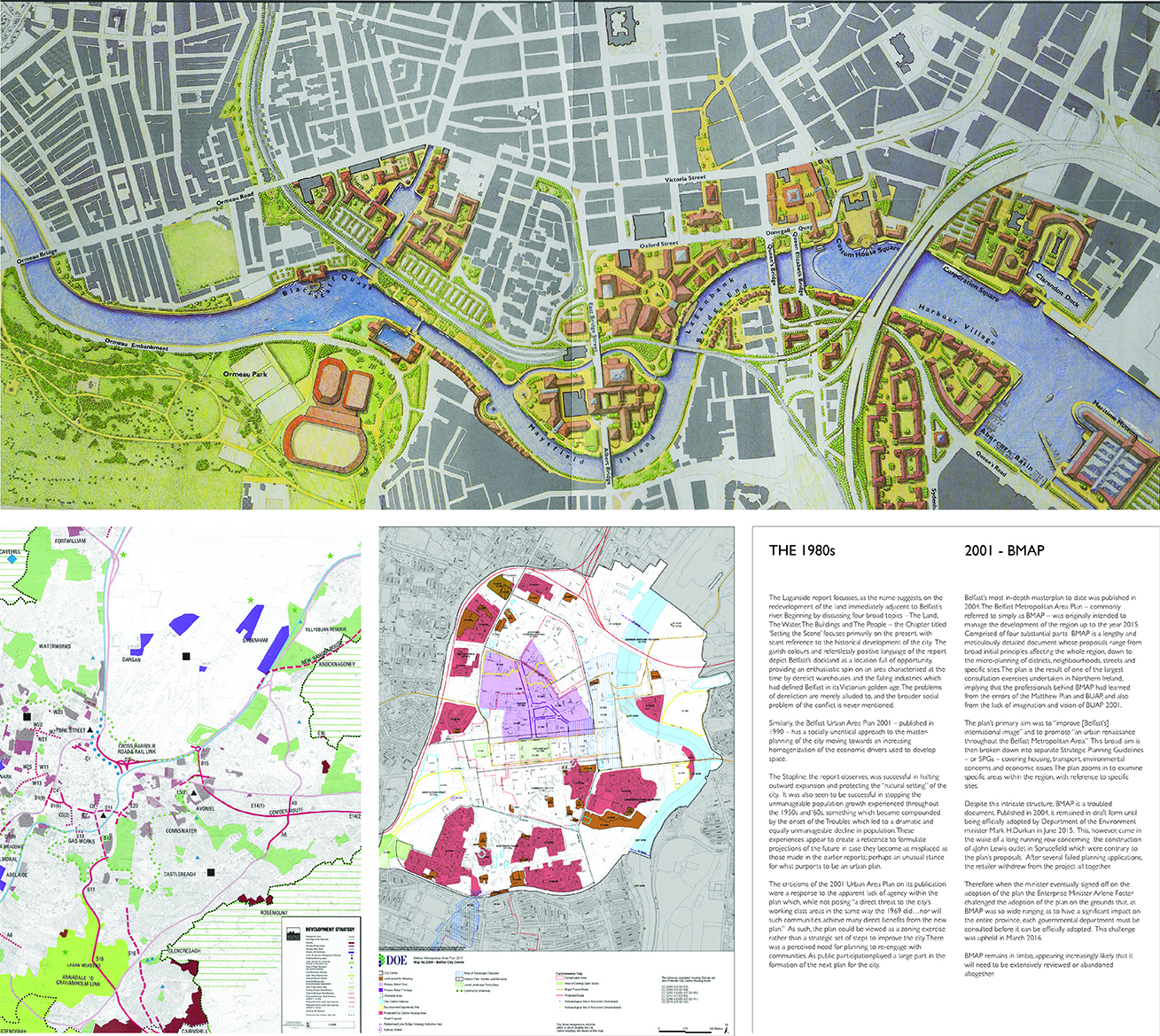

Commonly referred to as the ‘Davidge Report’ after the renowned architect-surveyor W.R. Davidge, Belfast’s first official planning document was published by the newly formed Planning Commission in 1945. Yjis report conceives of the city as a scientific object which can be mathematically ‘worked out’ to create a set of proposals relating to the location of industry, distribution of housing and the location of new roads and infrastructure. Despite this, the maps accompanying the report belie what appears to be a sensitivity with regards to the city in the application of these objectively reasoned proposals. The shaded land-use proposals of Map One (above) intricately plot areas recommended for residential, industrial and public/private open space with no description or explanation of how or why these locations have been selected. The intricacy of the proposals detailed in the map implies that a great deal of consideration went into them regardless of whether this thought is represented by the text of the report. Similarly, Map Two (left) shows an incredible breadth of thought regarding the city itself. Key routes are identified, possibly relating to the proposed ‘improvement’ of these approaches mentioned throughout the reports. Where these routes have been widened, the original map of the city has been retained beneath, constantly placing the proposals in the context of the existing city and serving to highlight what would need to be removed to accommodate these changes. This indicates a sense of duration which is not expressed in the text of the report. Planning activist Ron Wiener suggests that these plans were never fully implemented as the influx of new industry to replace the ailing shipyard and linen industries would create an imbalance in the “Orange System.” Despite this these reports, which were only ever advisory, set the scene for the plans which followed; the concepts of removing industry from the city and the development of road infrastructure was to dominate the planning agenda for the next thirty years and beyond.

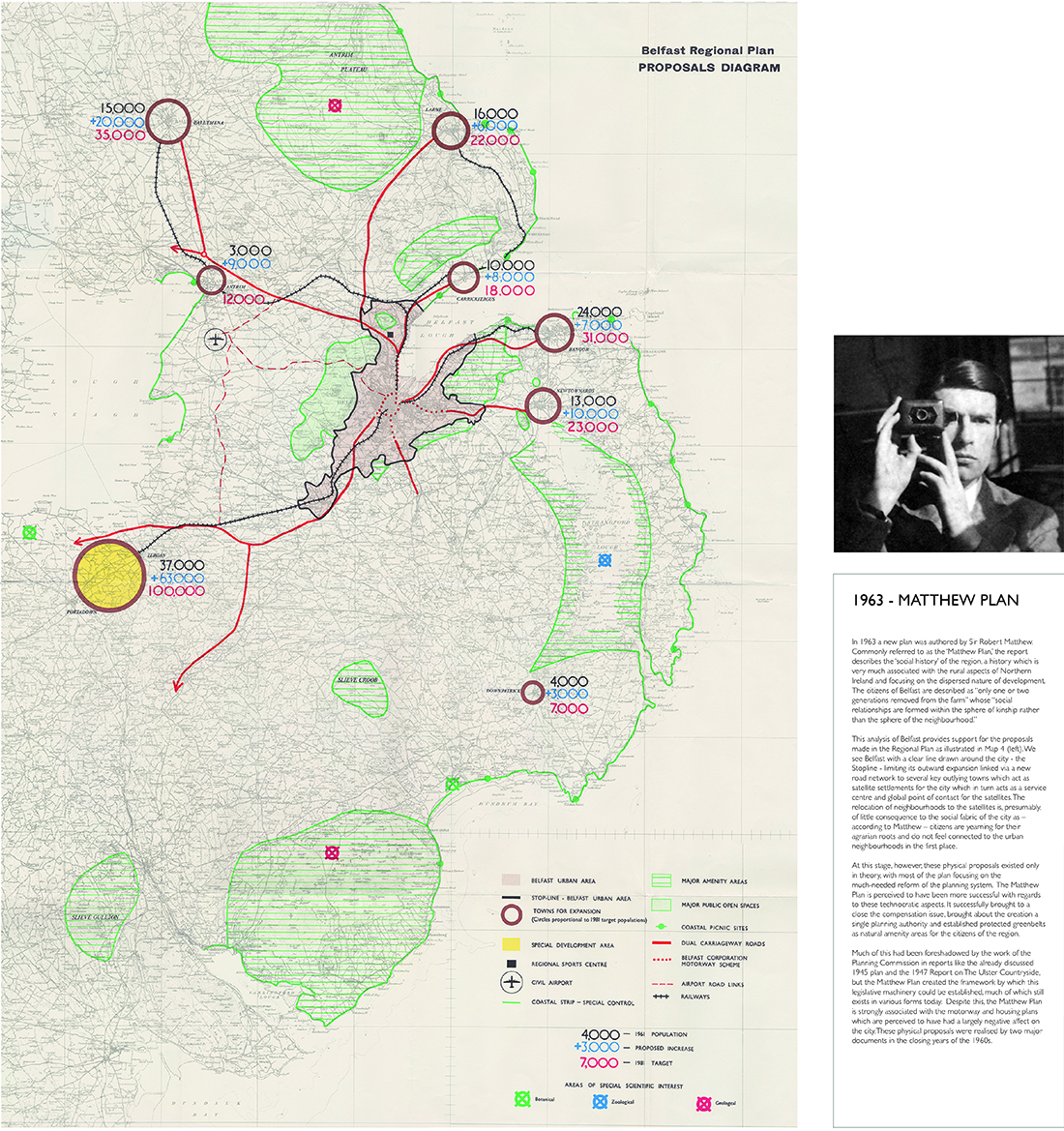

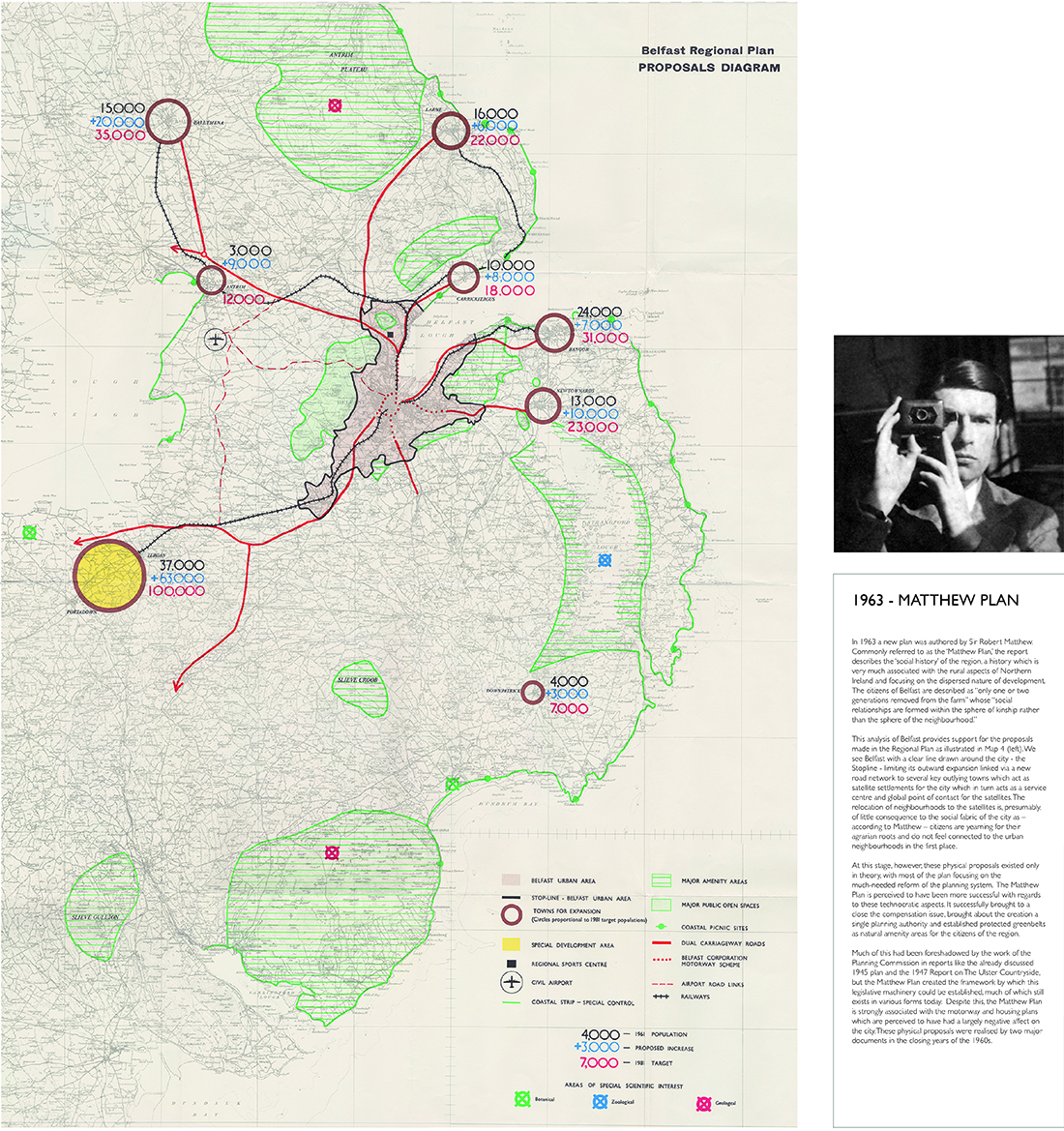

In 1963 a new plan was authored by Sir Robert Matthew. Commonly referred to as the ‘Matthew Plan,’ the report describes the ‘social history’ of the region, a history which is very much associated with the rural aspects of Northern Ireland and focusing on the dispersed nature of development. The citizens of Belfast are described as “only one or two generations removed from the farm” whose “social relationships are formed within the sphere of kinship rather than the sphere of the neighbourhood.” This analysis of Belfast provides support for the proposals made in the Regional Plan as illustrated in Map 4 (left). We see Belfast with a clear line drawn around the city - the Stopline - limiting its outward expansion linked via a new road network to several key outlying towns which act as satellite settlements for the city which in turn acts as a service centre and global point of contact for the satellites. The relocation of neighbourhoods to the satellites is, presumably, of little consequence to the social fabric of the city as – according to Matthew – citizens are yearning for their agrarian roots and do not feel connected to the urban neighbourhoods in the first place. At this stage, however, these physical proposals existed only in theory, with most of the plan focusing on the much-needed reform of the planning system. The Matthew Plan is perceived to have been more successful with regards to these technocratic aspects. It successfully brought to a close the compensation issue, brought about the creation a single planning authority and established protected greenbelts as natural amenity areas for the citizens of the region. Much of this had been foreshadowed by the work of the Planning Commission in reports like the already discussed 1945 plan and the 1947 Report on The Ulster Countryside, but the Matthew Plan created the framework by which this legislative machinery could be established, much of which still exists in various forms today. Despite this, the Matthew Plan is strongly associated with the motorway and housing plans which are perceived to have had a largely negative affect on the city. These physical proposals were realised by two major documents in the closing years of the 1960s.

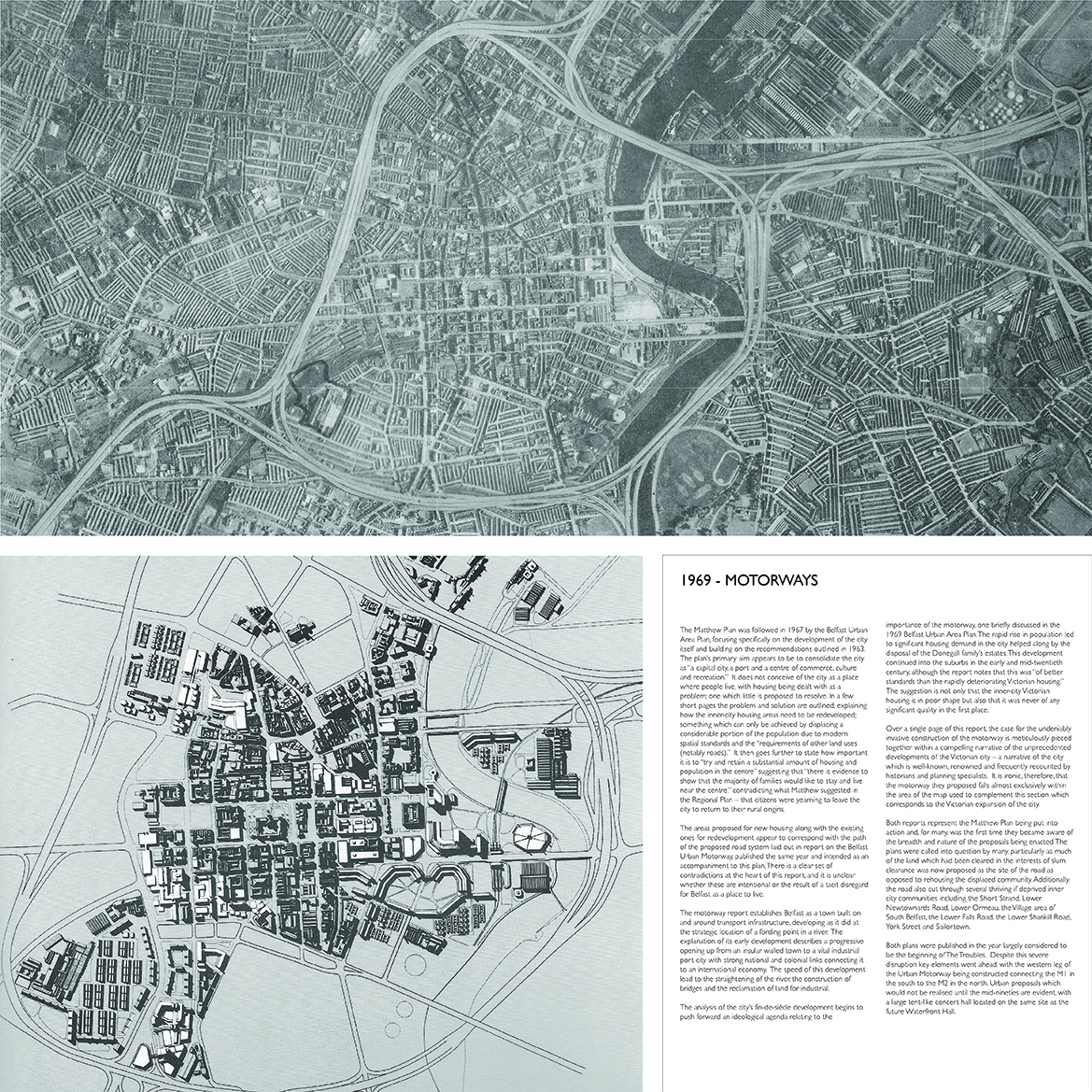

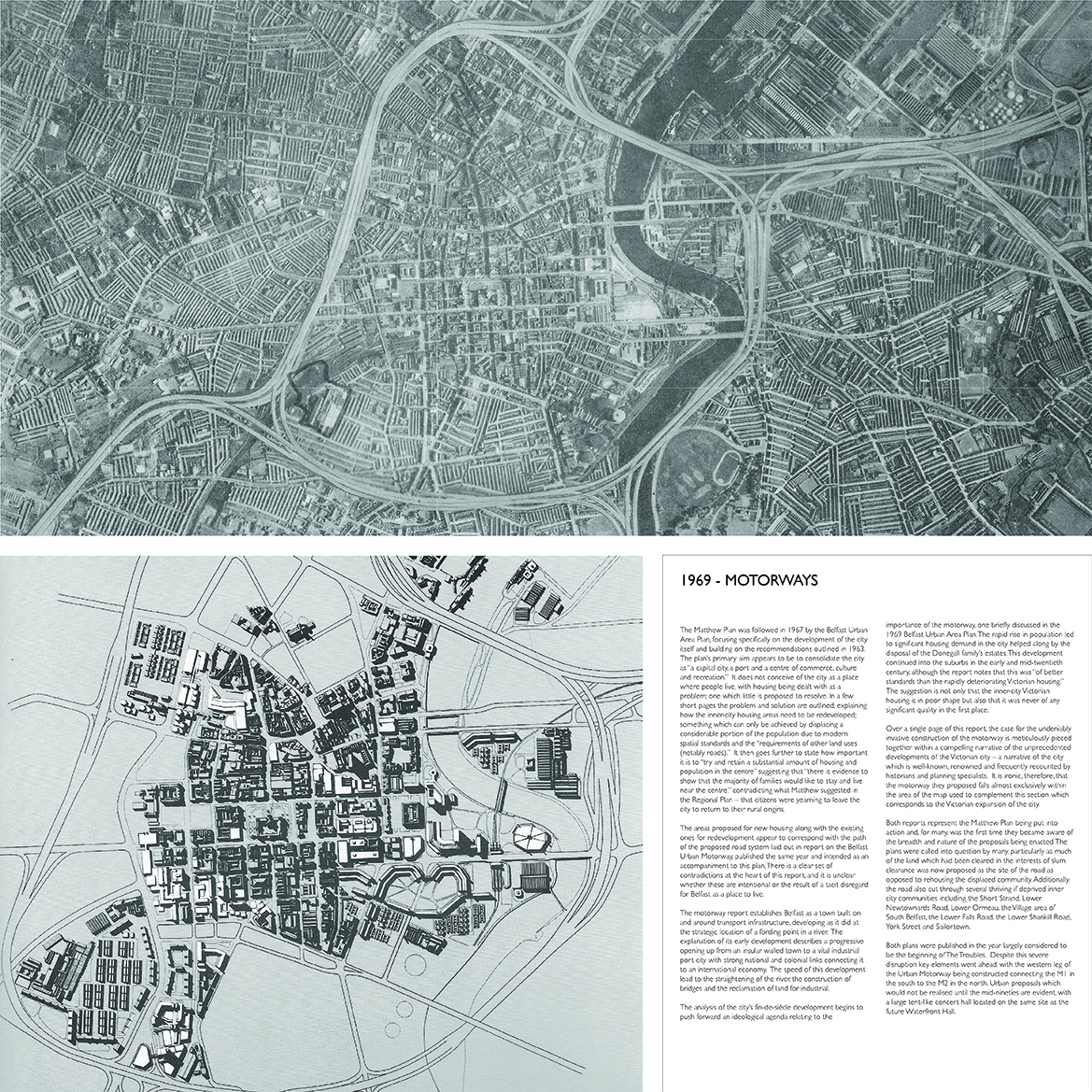

The Matthew Plan was followed in 1967 by the Belfast Urban Area Plan, focusing specifically on the development of the city itself and building on the recommendations outlined in 1963. The plan’s primary aim appears to be to consolidate the city as “a capital city, a port and a centre of commerce, culture and recreation.” It does not conceive of the city as a place where people live, with housing being dealt with as a problem; one which little is proposed to resolve. In a few short pages the problem and solution are outlined, explaining how the inner-city housing areas need to be redeveloped; something which can only be achieved by displacing a considerable portion of the population due to modern spatial standards and the “requirements of other land uses (notably roads).” It then goes further to state how important it is to “try and retain a substantial amount of housing and population in the centre” suggesting that “there is evidence to show that the majority of families would like to stay and live near the centre,” contradicting what Matthew suggested in the Regional Plan – that citizens were yearning to leave the city to return to their rural origins. The areas proposed for new housing along with the existing ones for redevelopment appear to correspond with the path of the proposed road system laid out in report on the Belfast Urban Motorway, published the same year and intended as an accompaniment to this plan. There is a clear set of contradictions at the heart of this report, and it is unclear whether these are intentional or the result of a tacit disregard for Belfast as a place to live. The motorway report establishes Belfast as a town built on and around transport infrastructure, developing as it did at the strategic location of a fording point in a river. The explanation of its early development describes a progressive opening up from an insular walled town to a vital industrial port city with strong national and colonial links connecting it to an international economy. The speed of this development lead to the straightening of the river, the construction of bridges and the reclamation of land for industrial. The analysis of the city’s fin-de-siècle development begins to push forward an ideological agenda relating to the importance of the motorway, one briefly discussed in the 1969 Belfast Urban Area Plan. The rapid rise in population led to significant housing demand in the city helped along by the disposal of the Donegall family’s estates. This development continued into the suburbs in the early and mid-twentieth century, although the report notes that this was “of better standards than the rapidly deteriorating Victorian housing.” The suggestion is not only that the inner-city Victorian housing is in poor shape but also that it was never of any significant quality in the first place. Over a single page of this report, the case for the undeniably invasive construction of the motorway is meticulously pieced together within a compelling narrative of the unprecedented developments of the Victorian city – a narrative of the city which is well-known, renowned and frequently recounted by historians and planning specialists. It is ironic, therefore, that the motorway they proposed falls almost exclusively within the area of the map used to complement this section which corresponds to the Victorian expansion of the city. Both reports represent the Matthew Plan being put into action and, for many, was the first time they became aware of the breadth and nature of the proposals being enacted. The plans were called into question by many, particularly as much of the land which had been cleared in the interests of slum clearance was now proposed as the site of the road as opposed to rehousing the displaced community. Additionally, the road also cut through several thriving if deprived inner city communities including the Short Strand, Lower Newtownards Road, Lower Ormeau, the Village area of South Belfast, the Lower Falls Road, the Lower Shankill Road, York Street and Sailortown. Both plans were published in the year largely considered to be the beginning of The Troubles. Despite this severe disruption key elements went ahead, with the western leg of the Urban Motorway being constructed connecting the M1 in the south to the M2 in the north. Urban proposals which would not be realised until the mid-nineties are evident, with a large tent-like concert hall located on the same site as the future Waterfront Hall.

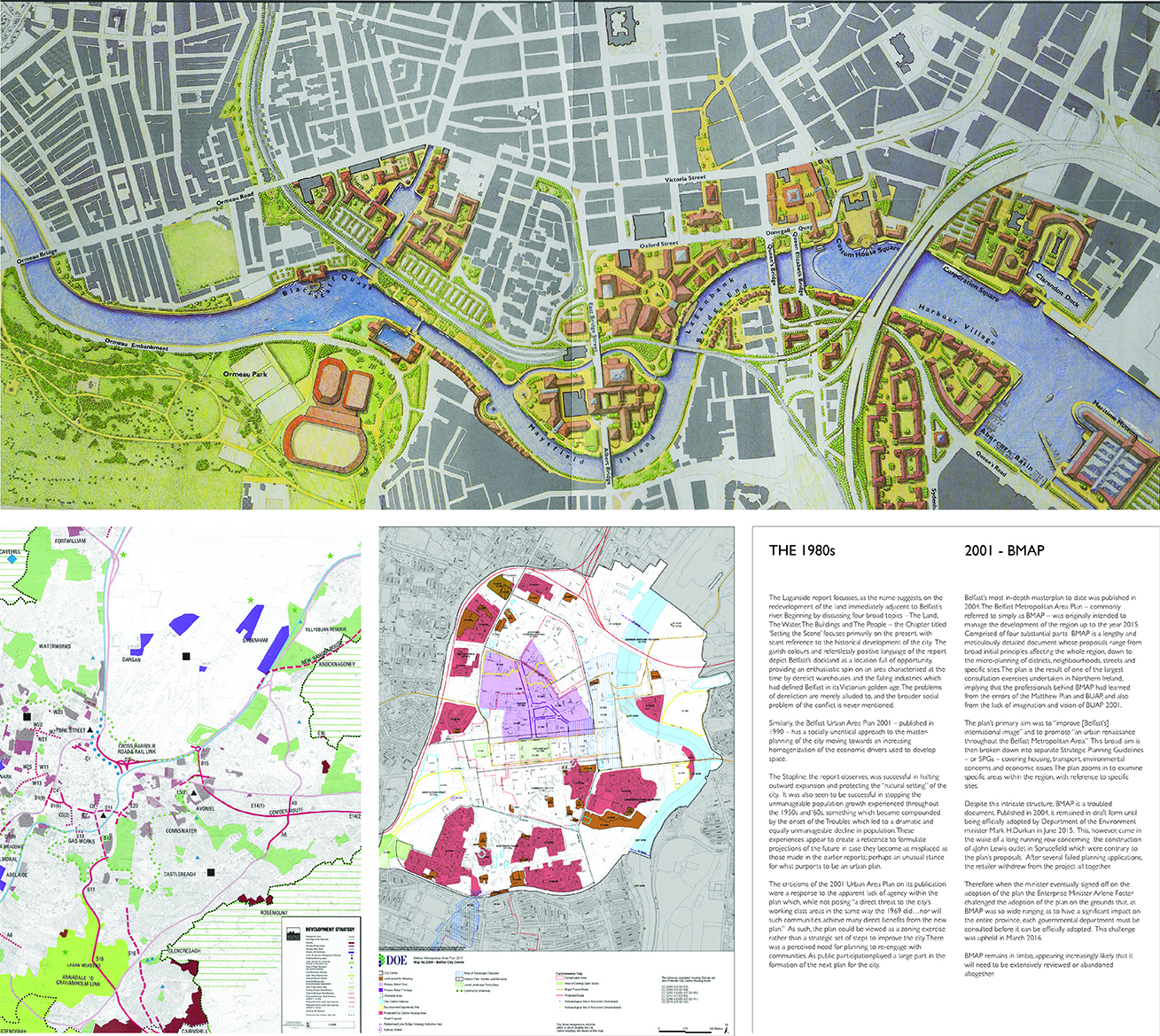

The Laganside report focusses, as the name suggests, on the redevelopment of the land immediately adjacent to Belfast’s river. Beginning by discussing four broad topics – The Land, The Water, The Buildings and The People – the Chapter titled ‘Setting the Scene’ focuses primarily on the present, with scant reference to the historical development of the city. The garish colours and relentlessly positive language of the report depict Belfast’s dockland as a location full of opportunity, providing an enthusiastic spin on an area characterised at the time by derelict warehouses and the failing industries which had defined Belfast in its Victorian golden age. The problems of dereliction are merely alluded to, and the broader social problem of the conflict is never mentioned. Similarly, the Belfast Urban Area Plan 2001 – published in 1990 – has a socially uncritical approach to the master- planning of the city moving towards an increasing homogenization of the economic drivers used to develop space. The Stopline, the report observes, was successful in halting outward expansion and protecting the “natural setting” of the city. It was also seen to be successful in stopping the unmanageable population growth experienced throughout the 1950s and ‘60s, something which became compounded by the onset of the Troubles which led to a dramatic and equally unmanageable decline in population. These experiences appear to create a reticence to formulate projections of the future in case they become as misplaced as those made in the earlier reports; perhaps an unusual stance for what purports to be an urban plan. The criticisms of the 2001 Urban Area Plan on its publication were a response to the apparent lack of agency within the plan which, while not posing “a direct threat to the city’s working class areas in the same way the 1969 did…nor will such communities achieve many direct benefits from the new plan.” As such, the plan could be viewed as a zoning exercise rather than a strategic set of steps to improve the city. There was a perceived need for planning to re-engage with communities. As public participation played a large part in the formation of the next plan for the city.

Belfast’s most in-depth masterplan to date was published in 2004. The Belfast Metropolitan Area Plan – commonly referred to simply as BMAP – was originally intended to manage the development of the region up to the year 2015. Comprised of four substantial parts BMAP is a lengthy and meticulously detailed document whose proposals range from broad initial principles affecting the whole region, down to the micro-planning of districts, neighbourhoods, streets and specific sites. The plan is the result of one of the largest consultation exercises undertaken in Northern Ireland, implying that the professionals behind BMAP had learned from the errors of the Matthew Plan and BUAP, and also from the lack of imagination and vision of BUAP 2001. The plan’s primary aim was to “improve [Belfast’s] international image” and to promote “an urban renaissance throughout the Belfast Metropolitan Area.” This broad aim is then broken down into separate Strategic Planning Guidelines – or SPGs – covering housing, transport, environmental concerns and economic issues. The plan zooms in to examine specific areas within the region, with reference to specific sites. Despite this intricate structure, BMAP is a troubled document. Published in 2004, it remained in draft form until being officially adopted by Department of the Environment minister Mark H.Durkan in June 2015. This, however, came in the wake of a long running row concerning the construction of aJohn Lewis outlet in Sprucefield which were contrary to the plan’s proposals. After several failed planning applications, the retailer withdrew from the project all together. Therefore when the minister eventually signed off on the adoption of the plan the Enterprise Minister Arlene Foster challenged the adoption of the plan on the grounds that, as BMAP was so wide ranging as to have a significant impact on the entire province, each governmental department must be consulted before it can be officially adopted. This challenge was upheld in March 2016. BMAP remains in limbo, appearing increasingly likely that it will need to be extensively reviewed or abandoned altogether.

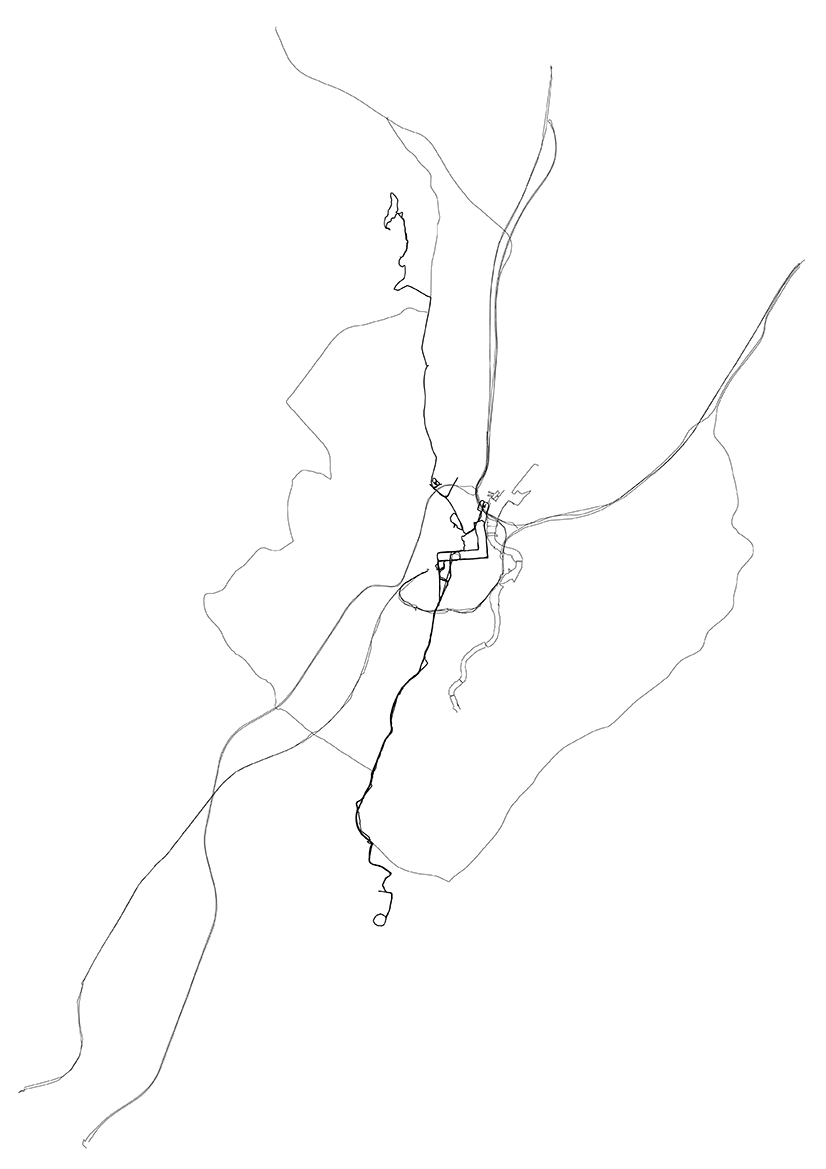

The rise of locative media has developed a new methodology for mapping. Used extensively for contemporary way finding, the Global Positioning System (GPS) enables walkers to “(write) over the earth…drawing with ourselves as we move.” Inspired by the art practice of Jeremy Woods, the researcher made several attempts at producing drawings using GPS. This method was used to draw a 1:1 representation of the city in as few lines as possible. Each line represents a specific theme, chosen to best represent key physical elements of the city; river, motorways and train line with the City Hall marked as a centre point (on display in window). The arbitrariness of these elements was offset by the experience of physically walking the routes in order to draw the lines. No element can be drawn without the physicality of being there to experience it, while the arbitrariness of the themes brings back a level of interpretation and mindfulness which the abstraction of writing text on the city in the previous experiment removed. The second GPS drawing (left) was influenced by Jeremy Woods’ My Ghost. Where Woods tracked all his movement in London for a decade the researcher, tracked all their movements across the city for six months between March and August 2013. This was an intense period of research activity and experimental drifts so the map shows a variety of different routes which are not normal activity for the researcher. This map is also presented as a series of perspex slides in a freestanding timber slide box., Each slide represents a month of movement around the city. Also on display are a series of excerpts from the researcher’s sketchbooks from key moments in the project.